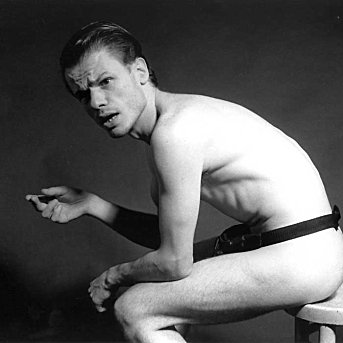

DILLON is side on, seated on a chair in the half light, his tortured profile etched with pain. He is naked and utterly vulnerable, his sinewy body twitching with emotion. “Take me,” he cries, “I’m lonely.” This is Hell, a searing and eternal isolation.

Say a Prayer for Me and Hell are from two short stories written by Steven Berkoff, adapted for the stage and performed by George Dillon. In the former, the failed actor Harry seeks to breath life into his tawdry existence by achieving a sexual liaison with the equally alone Doris. A brutal, disturbing piece, venom drips in Berkoffian language as the tale of bedsit degradation and humiliation unfolds.

In Hell, a haunting and eerie play accompanied by Harold Budd’s music, a man is consumed by a terrifying, gnawing loneliness in death as in life. It is a stark and chilling glimpse of the anatomy of despair.

One cannot be unaffected by Dillon’s virtuoso performance in this world premiere of Berkoff’s two monologues. It is a tour de force in which the actor and his material become one and the fusion of life and theatre is complete.

Toby Harnden, THE SCOTSMAN, 28th August 1992

There’s a definite buzz in the sell-out crowd for the opening of a new Berkoff by one of the most-praised solo performers of recent Fringes. George Dillon – who has a healthy pedigree of Berkoff collaborations – presents dramatisations of two of the great man’s short stories (one unpublished) alone on stage. This is appropriate, since the common theme is desperate loneliness.

In the first piece, Berkoff’s recurrent misery-guts Harry attempts a sordid seduction, with catastrophic results to fuel his sad misogyny. It’s wittily written and inventively enacted, but fairly predictable. Hell, however, is an astonishing contrast. If you thought Berkoff was all arch bombast, then try this mesmeric wade through the quagmires of despair, presented (almost) nude to the ambient tones of Harold Budd. From its monotone opening to its killer final line, it’s both unique and fascinating.

Not cheery, but definitely chunky

Andrew Burnet, THE LIST, 28 August 1992

HALFWAY through the week the temptation to organise a fringe version of Happy Families was overwhelming: bringing together the head of one show, the body of a second and the legs of a third. So often it’s either-or. Either performance skills or coherent narratives. Either psychological insight or offbeat humour. Couldn’t these groups shuffle the cards and get together? But there was one performance that had it all. It was a small irony that the double-bill Say A Prayer for Me and Hell was not listed in the Fringe programme. Also its eight performances take place at four different venues. Never mind. Long live last-minute plans.

George Dillon performs two stories by Steven Berkoff – the second of them unpublished – on the subject of loneliness. The first unmasks the creeping fears and failures of Harry, a mediocre actor, before and after he has sex with Doris, a plain girl at his hostel. Dillon switches with electric intensity between Berkoff’s grotesque voices, savage irony and unexpected tenderness. One minute Dillon shrivels up into a snarling, flailing embodiment of failure, the next minute he preens himself with a memory of a review in a local paper. This is a rapid, biting, fifth-gear performance.

Hell is more surprising. Dillon sits way upstage, in a red spotlight, virtually naked, and describes the crushing loneliness that engulfs him after a love affair. Dillon barely looks at the audience. He changes position a couple of times and inhales on a mimed cigarette. Harold Budd’s plangent music and Dillon’s amplified voice create a portentous atmosphere – one that could so easily slip into self pity – but Dillon controls this narrative with compelling assurance.

Robert Butler, THE INDEPENDENT, 30 August 1992

THE unbearable torments of the human condition are portrayed with such frightening realism by George Dillon that we are left squirming.

We see loneliness in each of these half-hour plays eating into the soul of Berkoff’s alter-ego like a cancer – and an individual powerless to stop the rot. And his nakedness in the latter, Hell, is symptomatic of a cruel vulnerability in each of us that has the capacity to destroy.

Dillon’s dramatic range translates the playwright’s work into mesmerising theatre well-capable of striking uncomfortable chords.

In turns funny, harrowing, real and surreal, this daring performance is nothing short of brilliant.

Jean West, EDINBURGH EVENING NEWS, 1st September 1992

Steven Berkoff’s close collaborator and ardent disciple, George Dillon, demonstrates, not for the first time, his sensitive and intelligent understanding of his mentor’s work in this provocative performance of two fiercely-contrasting Berkoff short stories. And in the process, Dillon also powerfully reminds us of the technical control, range and intensity that mark him out as one of the most distinctive and challenging solo performers around.

Say a Prayer for Me is a savagely humorous depiction of a fruitless, sordid brief encounter between unloved, unfulfilled people. Berkoff’s text mercilessly juxtaposes Harry’s dreams of celebrity on the stage with the reality of his life as a faceless employee in a gents outfitters, then dissolves Doris’ dreams of romance and security in the reality of Harry’s desperate, lunging attentions. Dillon combines the precision and timing of the practised storyteller with the physical expressiveness of the accomplished actor, to expose a rich if slightly predictable mixture of humour, anger, futility and human sadness.

In Say A Prayer For Me, Dillon stands back from the story, recounts, enacts and, in a sense, enjoys it. In Hell, he immerses himself in his material and suffers. The immediate impact of this sustained, uncomfortable evocation of loneliness derives from the bleak beauty and haunting truth of Berkoff’s text, qualities enhanced by the accompanying music taken from the work of Harold Budd. Dillon brings measured delivery, carefully-stylised visual imagery and above all the degree of physical and emotional vulnerability needed to translate powerful prose into disturbing, dangerous theatre.

Mick Martin, THE GUARDIAN, 26th January 1993

One-man shows are not my favourite. They tend to fall into two camps: the historically-exact recreation of the life of an 18th-century worthy, and the obsessive outpourings of a normally-out-of-work actor. Either way, it is difficult for a single voice and body to create the dramatic tensions that make theatre something apart from storytelling.

Difficult, but not impossible. George Dillon, one-man wunderkind and spiritual son of Steven Berkoff, is showing up the opposition in no fewer than four shows playing at the Pleasance. I watched his double-bill of adaptations from Berkoff’s short stories.

Say a Prayer for Me and Hell are visions of T S Eliot’s Wasteland for our times. Not recommended for those feeling unloved or isolated, they are meditations on the inhuman condition, sad portraits of those trapped in lives untouched by other lives.

The first is the unlovely love story of Harry and Doris, a couple who make Frankie and Johnny seem glamorous. He is an assistant in a suit-shop, all tissue-thin charm and dirty cuffs, who returns in the evening to soulless digs and nights in front of the telly. She is the cleaner, destined to a lifetime of mopping up after people she doesn’t know. Their tragedy is an age-old one: fear of self-revelation keeping them from the mutual salvation of love.

Despite appearances to the contrary, Berkoff is a romantic. He sees the human hearts beating under the grey masks of urban indifference, hears the echoes of ageless tragedies in the tinny reverberations of modern lives. These two little playlets are what our age can muster in the way of tragedy. Compared with more communal and heroic ages, our lives have shrunk until the one-man show is the best reflection of our society’s soul.

George Dillon presents these works with verve and fervour. In the first he is as mobile as protoplasm, flowing into the shapes and characters of bed-sit land in an extraordinary display of energy and control. The second piece appears more effective for its contrasting stillness. He sits, practically motionless, tinged with red light, like a bloodied version of Rodin’s The Thinker, and takes us on a journey into a personal inferno, just as bleak and affecting as anything Dante has to offer.

Julie Morrice, SCOTLAND ON SUNDAY, 15th August 1993

These three monologues are derived from short stories by Steven Berkoff, and are narrated by someone it is tempting to see as his shadow self.

There could be no more extreme contrast. Berkoff must be one of the least shy and shrinking performers in the history of the British theatre. But nobody would cast Harry, his actor-narrator, as the loquacious blimp in Decadence or the angry, alsatian-loving skinhead of One Man. He is frightened, failed and all those things Berkoff can only be in a secret blood vessel somewhere in the left ventricle of his heart of hearts.

George Dillon performed two of these playlets in Edinburgh last year, and now adds another, The Secret of Capitalism. In it, the actor talks of his possessions, from his house to his cat, his mortgage to his woman, and then launches into an equally soulless attempt to quantify his success on the stage. Why, if you tot up all the people who see him in a week, and then add their friends and their friends’ friends, it is possible that more than 125,000 may have heard of him during the past month. “I wonder why I’m often sad, lonely and desolate,” Dillon finishes in the blank, bewildered manner he often adopts.

That is the evening’s theme, message, lament, call it what you will. It recurs in Say a Prayer for Me, which finds Harry renouncing the stage, taking lodgings in an area “somewhere between purgatory and hell” and a job in an off-the-peg tailors, and lusting after a cleaner called Doris. She comes to his room, too, pathetically prepared to trade sex for friendship. The result is a crude, stupid fiasco that leaves both of them, especially him, more isolated than ever.

Dillon brings a certain verve and inventiveness to Harry’s histrionic fantasies, but his forte is a vulnerability we have not seen or suspected in his author.

That is why the last monologue proves to be the most successful, even though it is sometimes overwrought and entirely lacks the wry humour that surfaces in the other two. It is called Hell and, on the whole, merits the title.

Dillon spends it stripped to a black loincloth, sitting sideways-on in a plain chair, and bathed in a red light. Again and again, he talks of a loneliness that he feets other people, whom he seldom sees, must actually be able to smell. He still has his cat, but not his woman. It appears he drove her away with his morose introversion, his feelings of inadequacy, his dislike of fun and friends. So he takes a potion of tranquillisers and whisky and drifts into the hereafter, asking St Peter or whomever he meets to overlook his suicide: “You see, I’d quite like to meet some people here.”

Self-pitying, maudlin stuff? It could and perhaps should have been. But in his gentle, doleful way Dillon manages to summon up something as improbable as, let’s say, a garrulous Pinter or a hale and hearty Simon Gray: the Beckett in Berkoff.

Benedict Nightingale, THE TIMES, 24th August 1994

Steven Berkoff’s The Secret of Capitalism, Say A Prayer For Me and Hell are all concerned with the theme of loneliness. Performed by George Dillon, these three short tales make for a miserable yet marvellous evening. The first piece explores just how alone an individual can feel amid the crowds of society. Jauntily dressed in braces and loud shirt, Dillon begins the episode as a paragon of self-assurance. He owns a house, has lodgers, a woman and two cats, a bank manager, a dentist, an agent and a part-time secretary. Little by little, however, desperation creeps into his voice. He realises that, directly and indirectly, he is influenced by, and is an influence upon, thousands of people. He lists these people with an obsessive desperation, determined to prove his worth. But ultimately, though surrounded by many, he is alone.

Say A Prayer For Me is a sordid and humorous depiction of a humiliatingly brief and empty sexual encounter between two desperately lonely people. Failed actor Harry imagines himself in love with Doris, the cleaner in his digs. This infatuation fills his thoughts during the endless empty hours. But when the two finally meet, he is incapable of offering her either warmth or compassion. The irony is that if they could have harnessed their loneliness together they might have become invincible. But instead they separate, more hurt and damaged than before and with less self-esteem than when they met. It is insulting, pathetic and deeply human.

For the final piece, Hell, Dillon appears naked on stage, thus offering a physical depiction of the vulnerability he has hitherto expressed. He then takes it one stage further: his character desperately searches for companionship, and, when rejected, commits suicide. Even in death, however, he is alone, and we see him crouching miserably in some people-less purgatory trying to find a friend.

Dillon’s performance in all three pieces is extraordinary. He is raucous, humorous, pitiful and exceptionally tender. The three monologues, despite their linked theme, each possess a unique angle on the despair of solitude. Dillon opens up a chasm in the human experience, then stands at its bottom and screams. Seeming at times Ike a comic impersonator, he moves through a series of grotesque voices before suddenly hitting you with the force of his acting. All the anguish of the most harrowing performance is distilled into the little lives of these little people. The stage is empty, the subject matter almost banal, so there is nothing but the force of Dillon’s performance to carry you through. He does not disappoint.

It is particularly exciting to have these three pieces in London at the moment, These can be dry weeks in London, with everyone apparently up in Edinburgh. Here is a performance though which came out of Edinburgh in 1992, and cannot be too highly recommended to anyone in London now.

Louise Stafford Charles, WHAT’S ON IN LONDON, 31st August 1994