WITH his one-man interpretation of Steven Berkoff’s Hell and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Dream Of A Ridiculous Man George Dillon combined two haunting visions of the world in which we live.

In Berkoff s short monologue, the central character Harry paints a compelling picture of his isolation within modern society in which he has so little contact with other human beings that, when he dies, nobody discovers his body for four days.

In Dostoevsky’s strange play, the central character decides to kill himself but changes his mind after being transported to a world without sin where humans live in happiness and harmony.

Each play offered a bleak and thought-provoking view of the human condition with differing degrees of hope for the future.

Dillon’s fine performance kept the audience transfixed for an hour-and-a-half.

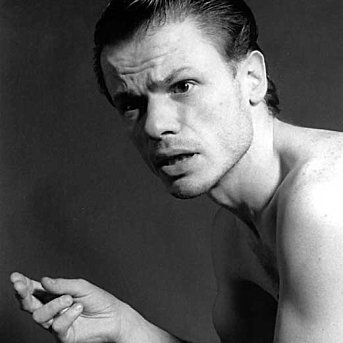

In Hell, he emphasised the loneliness and vulnerability of the central character, Harry, by performing the entire monologue as a solitary figure on a wooden chair in the centre of the stage wearing only a pair of pants. His recounting of his past attempts at human contact and his longing for a woman to hold and keep him company was deeply moving.

He was, by turns, humorous, self-mocking and even petulant as he described how his life had narrowed until he spoke to no one and spent his days smoking in his bedroom with only a cat for company. There was something most people could recognise in the portrayal of the vicious and debilitating circle of hopelessness and desperation.

In Dostoevsky’s feverish play, Dillon was strangely charming as the cynical nihilist who planned to shoot himself through the head but fell asleep instead and dreamed he was taken to paradise on a parallel Earth. There, he lived a joyful life, constantly amazed at the beauty and innocence of the human inhabitants until he realised his presence among them had fatally corrupted them, turning utopia into a tarnished replica of our Earth. When he returned to the grey reality of the real world, he changed his mind about killing himself and embarked on a crusade to persuade others of the truth of his vision and create a more caring world.

It was a manic and energetic performance during which the actor flitted from exasperated rant to matey anecdote-telling to anguished entreaties at a baffling pace.

Dillon’s virtuoso performance in both plays kept the audience spellbound.

Martha Buckley, THE ARGUS, 31st July 2001

George Dillon, who got my vote for best actor at last year’s Fringe, returns in 2001 with two short one-man pieces, Steven Berkoff’s Hell and the rather longer Dream of a Ridiculous Man by Dostoevsky.

Although they both deal with men who are on the verge of suicide, they are very different pieces. The protagonist in Hell is desperately lonely, never leaving the chair which is placed centre stage, whilst the character in the Dostoevsky piece – who knows he is a “ridiculous man” – is almost manic in comparison.Played one after the other, the two pieces showcase Dillon’s remarkable talents. It isn’t just the voice, superbly controlled though it is, but it is the physicality of his performance which impresses most. Even in Hell, confining himself, as he does, to a chair, every muscle talks directly to us.

If you want to see the craft of acting at its best, there’s no better place to go than here!

Peter Lathan, BRITISH THEATRE GUIDE, August 2001

Berkoff on the Fringe is nothing new; but there can be few actors who have brought such power to the old goat’s words as George Dillon. A compelling performer with an astonishing command of his abilities, Dillon seems not to know the meaning of the word “autopilot”. He’s fully switched-on at all times, weighing up every syllable and gesture for maximum impact. His Berkoff monologue, performed entirely from a dimly-lit wooden chair, is excellent, shot through with darkly comic touches and giving him plenty of scope for subtle shifts of mood. It’s when he moves to the Dostoevsky and is suddenly mobile that his barbed diction is matched by a very dangerous, unhinged physical presence. Two captivating performances which should not be missed.

Alastair Mabbott, THE LIST, August 2001

With only one show on my schedule for Saturday, I managed to take a bit of rest. But what a show!

I’ve started to think of George Dillon as kind of a theatrical surgeon. His acting is that precise. Every move, every gesture, every modulation of his voice is carefully chosen and exactly executed. And while you may think that calculation of this degree could make a show somehow soulless, the opposite is true. Case in point is Dillon’s Dostoevsky’s Heaven and Berkoff’s Hell. In Hell, Dillon (and Berkoff) create a very moving portrait of depression. The soundscape that accompanies Harry as he recounts his sad and tawdry life is perfect, galloping forward as he simulates energy, then slowing and pulling him back into his dark hole. In Dostoevsky’s Heaven, we meet a man preaches the golden rule with truly jaw-dropping zeal. Two powerful performances by a brilliant actor!

Kate Watson, THE SCENE (HALIFAX, CANADA), 12th September, 2011

I try not to overuse the phrase “tour de force” because I think that it is typically made commonplace as reviewers rush to use it in the depiction of nearly every single performer show. Yet, George Dillon, a star of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival who has descended upon the Atlantic Fringe Festival this week with four very distinct one man shows, gives me no choice but to herald him a “tour de force” and to mean it from the bottom of my heart…

The third show that George Dillon performed, back at the Neptune Studio Theatre, was Dostoevsky’s Heaven & Berkoff’s Hell. In the beginning of the piece Dillon began sitting sideways on the stage clad only in his underwear, in murky light, as vulnerability personified. This man, one slowly dying of loneliness, is, I think, Dillon’s most haunting character. He speaks with such measured, clear diction, his voice heavy, sensitive and rapt with melancholy that, even when it fleetingly ebbs, hangs like a storm cloud unmoveable from his midst. Berkoff’s words bring us vividly and empathetically into the core of heartbreak and depression, a place that we have all rested upon from time to time and Dillon inhabits it so profoundly and delicately, he withers and crumbles before our very eyes.

In contrast, in Dostoevsky’s The Dream of A Ridiculous Man Dillon truly embraces the ridiculous mixing a dark sense of humour with the tale of the corruption of the innocent, a performance that is reminiscent of his portrayal of Christ, but with an even more unreliable protagonist. I found this piece the most challenging of Dillon’s work (thus far) because his reason for choosing to play his emotions in such an extreme, dramatic, and stylized way was not as apparent to me as with The Gospel of Matthew and The Man Who Was Hamlet. After having connected so ardently with the man in Berkoff’s Hell, it was arresting to be then so removed from Dostoevsky’s Heaven. Yet, it was also interesting to be placed in a position where one relates immediately to the man in Hell, but cannot do the same with the one experiencing Heaven.

George Dillon is a fascinating and intensely smart performer. Truly, I have never seen anyone else perform this kind of one person show and especially with such mastery and singularity. To be treated to four different ones all in a row is a rare and exquisite theatrical treat that I am most grateful to have experienced.

Amanda Equality Campbell, TWISITHEATREBLOG.COM, 11th September 2011