A father’s ghost, a mother quick to remarry and a servant slain – Edward de Vere’s story has many parallels with that of Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

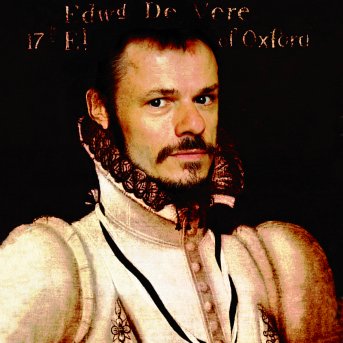

Actor George Dillon inhabited the role of the 17th Earl Of Oxford, a courtier, swordsman, adventurer, playwright and poet, whose ghost arose to tell his story.

If we are to believe Shakespeare based Hamlet on de Vere, or even that de Vere was Hamlet’s author, then this was de Vere’s revenge.

Fragments of the play were interspersed seamlessly with original writing – for example, de Vere’s silent grief for his father and the Polonius-like William Cecil’s advice to his ward to “neither a borrower nor a lender be”.

Even the young William made an appearance, with de Vere admonishing the boy for not learning to read or write. He later, rather foolishly, offered him one of his sonnets to use to win back his wife.

The play had its lighter moments – not least when de Vere, commencing, “To be or not to be…”, was cut off by William exclaiming: “What kind of question is that?”

What kind of question, indeed, for de Vere’s story was not a revenge tragedy but one more familiar to its 21st century audience – one of advancement, and the legacy we leave behind.

With an impressive performance by Dillon, simple but effective lighting, and a score performed by Charlotte Glasson on multiple instruments, including a saw, this was a big production in a small theatre and a cut above your average one-man show.

Joanne Davis, THE ARGUS, 3rd December 2008

FringeReview caught up with George Dillon, creator of Graft and The Gospel of Matthew; the man about whom Steven Berkoff said: “…The best example of someone to watch how to perform is George Dillon…”

Breakfast in Brighton with George Dillon! And a discussion about “The Man who was Hamlet – this was an opportunity too good to miss. Dillon is back in 2009 with his one-man performance format, something he has done so well over recent years. Dillon presents in The Man Who Was Hamlet a combination of many-character performance, with historical exposition exploring the ‘real’ identity of William Shakespeare, proposing Edward de Vere as the real author of Hamlet and much (if not all) of the rest of the Bard’s repertoire.

I managed to see an early version of this new production, ably directed by Denise Evans, at probably the best studio theatre space in Brighton, the New Venture Theatre.

Dillon took the square performance space and presented it in a diamond format, with audience fanned out from one corner and Dillon making full and intelligent use of the space provided by the opposite corner. This enabled him to play very effectively with opening out the space as he story-told us through much historical detail via a mix of comedy and highly intense scene-playing as we journeyed through a broad history as well as the biography of de Vere himself. Then Dillon would retreat into the furthest corner from us, the light diminishing, and we shared his prison cell in the Tower.Paul Levi, FRINGEREVIEW.CO.UK, JANUARY 2009

This is a piece in its early stages of development, an exciting piece of writing, witty and sharp, making delightful use of Shakespeare’s own lines in ways ironic, comedic and sometimes philosophical. Dillon has created a dramatic charger he has yet to fully mount but this is a piece in its earliest stages and, as usual, we were treated to a masterclass in delivery and individual performance.

There is nothing new about conspiracy theories, one of the most famous of which is that the Bard of Stratford upon Avon did not write the plays that bear his name.

The trouble is, nobody has yet come up with a wholly convincing alternative although George Dillon makes a good stab at bringing Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford into the picture.

This one-man play creates, with much skill, a potted biography of the aristocratic Englishman told with well-chosen snippets from Shakespeare’s plays, in particular that of Hamlet, whose story bears some resemblance to that of de Vere.

With dramatic effect, Dillon paints a picture of a cultured though arrogant man whose relationship with Queen Elizabeth led him into turbulent waters including being incarcerated in the Tower.

What becomes clear as the story unfolds is that de Vere’s life makes a good drama even without the Shakespeare theory, much of which is debatable anyway except to the most devoted Earl of Oxford fan.

Not mentioned is why such a man as de vere – who was known in contemporary circles as a respected poet – would wish to conceal his authorship of such masterpieces as Shakespeare’s plays.But the play’s the thing and Dillon does a neat job of presenting the eventful life of an Elizabethan courtier who was born into privilege and power but who squandered both with a lifestyle that would do credit to any number of today’s mega-rich celebs.

With gently atmospheric live music from Charlotte Glasson, the production is an interesting diversion around a debate that will probably continue to rage for generations to come.

Marion Cox, DORSET ECHO, January 2009

The title of George Dillon’s latest one-man performance sets out its wares but also begs the big question. As any ‘Oxfordian’ will tell you, while the hero of the piece, Edward de Vere 17th Earl of Oxford, may quite feasibly have provided the prototype for some aspects of Hamlet, he is also front-runner to have actually written the plays of Shakespeare (always assuming, that is, that you’re not one of those ‘Stratfordians’ who persist in believing they were penned by the comparatively obscure figure of William Shakespeare. There is also a Baconian party, but the feasibility of their candidate would seem to be on the wane in recent debates.)

Dillon didn’t quite lead us down that path, though it was left seductively open to view. It wasn’t really necessary to engage with such controversial issues when the raw historical material is already so richly-laden with politics, romance, treachery, adventure and the unassailable ego which was obviously the birthright of the aristocratic Elizabethan male. It says a vast amount for Dillon’s performance that it engaged his audience in such a satisfying way with a character who was pretty despicable in modern terms (though the excuse that he couldn’t attend his first wife’s funeral because he was off fighting the Spanish Armada does have the ring of period authenticity to it.)

It’s easy to see why Dillon’s performances have made him the toast of the Edinburgh Festival. This was pared-down, intimate theatre demanding sheer bravery on the part of the actor, who takes the stage armed with nothing more than a skull, a rapier and an elaborate set of lighting cues. A neat beard and a big shirt will do wonders to focus our attention, however, for with such minimal accoutrements he convincingly presented himself as a man whose expectations were as unquestioningly Elizabethan as his manner was direct and absorbing.

The journey through Oxford’s life isn’t an easy one to boil down into a soliloquy, so the evening was a virtuoso display of dramatic range that never risked coming close to over-statement or caricature – unlike his subject, Dillon is a master of subtle, unspoken control. Oxford was twelve when his father died and his mother remarried with unseemly haste, so the story starts with an arrogant, bewildered boy, aware that he is being shunted out of his family, but never relinquishing a jot of his aristocratic status and identity. A royal ward educated in the house of Sir William Cecil (whose daughter he married with less than harmonious results), he became a curious mixture of Renaissance Man and upper-class lout, and it was fascinating to see gradually revealed an individual who could encapsulate all the gentlemanly arts while nonetheless cherishing a concept of honour that sounds dangerously close to piracy.

Later in life (he died at 54), having travelled all the recognised routes to glory and self-fulfilment and found them disappointing, Oxford found solace and involvement (not to mention royal approval) with the acting companies to which he stood patron. But did he also find time to write the plays that survive under Shakespeare’s name? It was cunningly left to the words and circumstances of the piece to suggest this argument without polemic. Cecil’s advice to the aspiring young man was a brilliant example of this technique, with the sentiments of Polonius’ homily to Laertes recast into an entertainingly uncanonical, yet recognisable, variant. One Will Shakespeare is, however, mentioned – as an egg-headed boy of no book-learning who eventually finds his way into Oxford’s household en route from a shrewish wife for whom he cannot write poetry.

The enthusiastic response to this game did defuse the one issue I might have taken with the piece – how well are you expected to know your Shakespeare in order to appreciate it? The audience at South Shields was clearly appreciative, and though many of the textual references were obviously being picked up, I suspect that essentially it was the performance itself which impressed. Afterwards I heard someone describing the courage of Dillon’s acting, and certainly in theatre of this direct and unadorned kind, there isn’t a safety-net. The clarity of delivery, assurance of movement and generosity of spirit which characterised the whole project were so rewarding that I feel like an absolute churl when I say that I’m still rooting for Will from Stratford as the onlie begetter of those everlasting plays.

Gail-Nina Anderson, THE BRITISH THEATRE GUIDE, February 2009

My wife Jane, on the distaff side of my de Vere marriage, (the opposite side is known as the “spear-side”) loved and was intrigued and fascinated by George Dillon’s one-man play: This is important.

The menials and cleaners in recording studios were at one time known as the “old greys”. When they were caught whistling any new tunes they had picked up while they passed by with their mops and buckets, this was taken as an omen that the song would be a hit. The song had passed the “old grey whistle test”. This is important, because an unforced and natural opinion is reliable.

As members of the partisan coterie that is our de Vere Society we are often invited to credit a certain amount of dogged lunacy that makes up in effort for what it signally lacks in scholarship; but because we are so few we have to hold our tongues. I say this so that you might not discount my praise when I say of a fellow member that this is a definitive and marvellous work.

George Dillon, on stage as one-man band, impresario, lothario and Horatio has written a remarkable biography of our hero. With little more than Yorick’s skull, a big red book and a beautiful sword, his experience in playing Hamlet on the stage towards the end of the last century informs every crisply penned and spoken line. The understated lighting and the music for the performance were incisive. The whole performance in every single detail is the journeywork of one with a lifetime devoted to the stage, and one with a determination to give Lord Oxford his just dues.

Silent and riveting, the opening swordplay is the work of a master hypnotist. Before long you are taken upon the edge of his rapier into a new and an enlightening world. Any person who, bit by bit, becomes convinced that the husband of Ann Hathaway could do little more with words than sign his name in order to deprive her of a decent bed, knows that it is hard work and a long journey to become steeped in the Elizabethan world enough to divine that another was behind the works of Shake-speare. So this immaculate play is demanding. You will want to see it again. It will serve as an introduction to the heartbreak that informs the life and work of Edward de Vere, even if you think you know all about it; and because it is such a piece of work I entreat you to check when the play will be performed near you.

George told me that he had written the play in blank verse. This is clear if you have a sight of the text, and it explains how it is that the words on the stage can be delivered with such power. The language is taut; a simplified and succinct “Shakespeherian rag” that mixes the text of Hamlet in with the life of Edward de Vere so that it convinces; and in an entertaining and very creative way juggles with the known history of our nobleman.

Mr Dillon wrote the play, designed the adverts, printed the flyers paid for the set. Most of all George acted all the myriad parts, Elizabeth, DV, Ghost, Hamlet etc. He has a beautiful voice, a commanding presence and is a practised and wonderful swordsman.

George Dillon. After George Clooney and Bob Looney, what a marvellous name for a playwright and actor! I first spied him in the midst of the throng all beset with cramp trying to get warm after sitting through the AGM draughts of Castle Hedingham. At the time, he being pierced and penniless, we were pressed into giving him a lift back to the south. He turned out to be a rather earnest companion, theatrically depressed at this time at the course of his life. A year later, I reminded him of this, at The Surrey History Centre, the day after we saw his matchless play, but he had forgotten it all.

So to see this play in its finished form defied my expectations. In the context of what passes for drama in the modern theatre it was so startlingly well-crafted that it was a revelation. I now know more of the man and the jumbled wings that we carried south in our car. He had been at work on this play. It was an Icarus that we carried to sanctuary after he had fallen from the skies of inspiration. The Man Who Was Hamlet will, I hope be the work that will allow his reputation to soar; a trajectory the more transcendent because it started so low may be seen one day for what it is, a comet we return to, up there with the journeywork of the stars.

John Gill, THE DE VERE SOCIETY NEWSLETTER, May 2009

George Dillon is a firm believer that William Shakespeare did not write – indeed could not have written – the plays and poetry attributed to him.

This comes through subtly but unequivocally in his engrossing one man show, The Man Who Was Hamlet.

Speak to him offstage and he will explain in detail his well-researched view that, although there are other contenders, the Bard’s works were, in fact penned by Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.

Dillon brings his colourful, volatile subject strikingly to life, with no props except, appropriately, a fencing sword and a large book, plus an ever-present skull, to which no direct reference is made.

Born into a noble family with its lineage stretching back 500 years, de Vere was orphaned and took his title at the age of 12.

He became a courtier, entered into an arranged marriage, abandoned his wife (with whom he was later reconciled), travelled abroad, was held by pirates, fathered an illegitimate child, fell out of favour with Queen Elizabeth and was briefly imprisoned in the Tower.

He was later reinstated at Court but dedicated his later years to literature and died, virtually bankrupt, at the age of 54.

The actor not only personifies de Vere from near childhood to his heavily dramatised Hamlet-inspired death speech but also takes on both sides of numerous conversations with the queen and with others who cross his path. His confrontation with Sir Philip Sidney, a rival at Court, shows his flair for mimicry and his tirade against him a master-class in invective.

Solo productions can be static affairs but this play is physical by any standards. Dillon used every inch of the stage at The Hawth – unusually large by studio standards – in his agile sword-play and other activities to depict his subject.

The show, directed by Denise Evans, is enhanced by intelligently focused lighting and by Charlotte Glasson’s evocative music.

A thought-provoking evening to anyone with even a passing interest in Shakespeare and an enquiring mind.

Tony Flook, SURREY MIRROR, May 2009

A MAN. A STAGE. A TIME FOR PERFECT THEATRE.

George Dillon is an exceptional actor. Not one mistake – he plays all the characters, which means changing pitch and the way of speaking as well as the language within split seconds.

Did Shakespeare ever write? Who was Hamlet? Did they even exist? Who was behind the name Shakespeare? Was it a collective?

Who is really telling the story here? Is it Hamlet or Shakespeare? It is not George Dillon, that’s for sure. He is all the characters he embodies on stage. This play doesn’t need a lot of props. Back to basics is the motto and so it is just the actor and a sword.

The play is especially interesting if you know the plays, as it is full of quotes and hints – funny at times and deadly serious in parts.

The music fits the scenes well and underlines the words. You can feel Dillon’s commitment and enthusiasm for acting. An evening of theatrical pleasure that leaves you inspired.

Nadia Baha, NERVE, February 2010

The works and life of William Shakespeare are subject to all manner of literary and historical debate. The subject of who the man really was, his sexual preferences, his background and where he learned his craft, and which, if any, of the works assigned to him really are his still interest us. It is the latter topic that is addressed in the very imaginative The Man who was Hamlet.

George Dillon performs a one man play that is brilliantly scripted and packed full of historic and literary references to not only Hamlet, but many of Shakespeare’s other works. Dillon plays the part of Edward De Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford.

The play explores the possibility that Hamlet may have been based on De Vere’s life, or that De Vere may have actually been Shakespeare himself, and that the writer we think we know may have been the illiterate son of a glove-maker. The illiterate ‘William’ makes a brief and comical appearance in the performance. We see Dillon’s De Vere rise from the grave to tell his story: the story of his life as an adventurer, swordsman, adulterer, and secret playwright to the court of Queen Elizabeth I. The story of his life is the story of Hamlet rearranged, part historical fact, part literary fantasy.

Dillon’s performance is excellent, making use of only three props and the small stage. The writing is witty, and the content extremely well researched, incorporating Shakespearian references, characters taken from Hamlet (Polonius appears as an interfering old man called Cecil, among others) and original Shakespearian lines.

Dillon’s acting range is varied and keeps the audience engaged throughout, and even if you have only a passing interest in Shakespeare, the performance is likely to keep you entertained for the ninety minute duration. However, an in-depth knowledge of Shakespeare and the literary theory surrounding him would have made the play a much more satisfying, amusing and gratifying experience.

Some of the audience I suspect missed many of the subtle references, puns and nods to the literary and historical debate around the story of Shakespeare and De Vere. I know I did! I found myself racking my brains for forgotten facts I learned whilst doing my literature degree, and I studied Shakespeare. I realised much of the audience were in the same boat when a much too loud laugh echoed around the auditorium in response to the really familiar references; ‘To be, or not to be’ was understood by all, and I got the feeling the audience were, in general relieved to identify something recognisable.

Taken simply as entertainment, the performance is interesting, well acted, brilliantly written, and a unique take on something we all have some basic knowledge of. But to do the play and its writing justice, you will definitely need a much more thorough familiarity with the bard who may, or may not have been, William Shakespeare.

Natalie Burns, GUIDE2BRISTOL, 5th March 2010

The better the performance, the harder to review. Why? Perhaps because of the daunting responsibility on the reviewer to match up to the standard set. This is the case with George Dillon’s solo piece The Man Who Was Hamlet, and if you haven’t time to read any further, let me say unequivocally that if you take a trip to the Hill Street Theatre at 19.10 any evening you will be rewarded with a 5 Star performance. This is acting as it should be – so you don’t notice it. Who was Shakespeare? Argument has, is and always will, rage, and one such claimant is Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Here in Edinburgh during the Festival the naughty, noble Earl will nightly, and in the most subtle, extremely well-informed and convincing way, tell you – no he won’t, he will allow you – to deduce that it was he who was really Him. Well it could have been – after all he was highly literate and articulate, had two theatre companies himself, had frequently entertained the Virgin Queen, was a considerable favourite with her – and at the end of his life as courtier/soldier was given no less than £1000 per annum by Elizabeth to do with as he wished……..and as he had so frequently been asked to perform for her or arrange entertainments, that could well have been to pen Hamlet et al. It could also of course have been to spy for her: that was the anonymous way things were done in that egg-shell age.

Dillon’s performance is truly masterly: no actorish egotism, nor meaningless, self-indulgent vocal mannerism , no “I am a star, worship me” here: from the moment this amazing monologue began the actor disappeared in humble subservience to the character, his subject. When I walked into the theatre and saw a bare black stage with just two simple props, a book and a skull – I knew we were going to get to the economic heart of the matter. The book was used once and the skull not at all – a witty neglect in itself.

The House lights fade to black: a spot comes up on an Elizabethan performing a silent sequence of rapier thrusts and parries – elegant, balletic but no mere courtly wafting, but essential knowledge and practice which could be used as well to kill as to charm. Dillon has researched his piece with great thoroughness and intelligence going back to original sources: he resists the temptation to be didactic: like a detective approaching a murder scene.

Dillon simply puts before us the key questions…. who had the motivation to write ‘the Works’? Who had the opportunity and who had the ability? – and lets the conundrum rest with us. I may be shot for saying this, but I don’t find the quality of Dillon’s voice remarkable – but the important thing is he uses it remarkably well. Not only his range, but also the split-second switch from one character to another is electrifying. He truly embodies in this performance the full spirit of Elizabethan adventure whether the scene is Courtly, piratical or poetic, womanising, wilfully adventurous or literary, we get a real feel of the first Elizabethan age……and Our Will is politely, kindly patronised as an ‘egg-headed wight’ – write Hamlet? No! Not even his own name! Wicked!

Richard Franklin, FRINGEREVIEW.CO.UK, 8th August 2010

Did the son of a glove maker from Stratford write Shakespeare? Not according to George Dillon, who in this one-man-show plays Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford – the real genius behind star-crossed lovers and the suicidal Dane.

Sigmund Freud, Orson Welles and Sir John Gielgud are amongst those who have favoured de Vere’s authorship, and next year Derek Jacobi and Mark Rylance star in Anonymous, a film which promises to settle once and for all why the bard couldn’t possibly have been a chav.

Dillon, to his credit, has got there first, and his literary aristocrat is as rogueish and charming as Rowan Atkinson’s Blackadder II (who, more orthodox scholars maintain, has just as realistic a claim to the authorship).

Regardless of who wrote what, Dillon’s performance is exceptional. As well as portraying de Vere at all ages and states of mind, he imitates numerous characters including Pope Pius V and Elizabeth I. He plays them all for laughs but none laughably. Most beguiling is his rendering of the simple and illiterate William from Stratford whom de Vere charitably helps with his poetry.

The action scenes are just as impressive. One man acting out fencing scenes and storms at sea could easily look ridiculous but Dillon pulls it off.

It possibly runs a tad too long and the moments of self-pity, though played well, occasionally jar with the piece’s otherwise impeccable pacing. Yet, whatever you think of the historical authenticity of Dillon’s claims, his de Vere is entirely believable.

James McIrvine, FESTMAG.CO.UK, 12 August 2010

Rising from the grave after Hamlet’s death scene, George Dillon draws the audience into an absorbing and thought-provoking one-man show. He takes one of the world’s oldest literary mysteries and turns it into an Elizabethan drama. Shakespeare scholars may shake their heads, but the evening’s a romp, and a clever one.

The simply-staged show is in the award-winning, relaunched Hill Street Theatre – a welcome newcomer on this year’s Fringe, committed to quality theatre in all shapes and sizes, with former Aurora Nova manager Tim Hawkins as its venue director. Like Hawkins, Dillon is a notable Fringe player, in his 14th year, with award-winning productions like Graft – Tales of an Actor under his belt.

Dillon’s central character is Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, swashbuckling swordsman and seaman, poet and theatre patron, noble and flirtatious courtier of Queen Elizabeth I, whom he plays from childhood to his mysterious withdrawal from public life.

He segues nicely back and forth into others along the way, particularly the Queen herself, regally wrangling with de Vere all the way from her bedchamber to the Tower.

We begin with the earl as a 12-year-old, struggling with a torrid emotional response to the death of his father and the rapid remarriage of his mother, where Dillon begins to introduce the idea that de Vere’s life was an inspiration for Hamlet. With it he reminds us that Hamlet’s story is not some distant drama of Denmark but a universal human conundrum.

It’s a leap from there to a much bigger conceit, which I won’t spoil. But one of the evening’s most amusing moments is the encounter between de Vere and a bald-headed bumpkin who like himself has a wife called Anne, and is named William.

Tim Cornwell, THE SCOTSMAN, 19th August 2010

Once, years ago, a friend of a friend asked me if I wanted to come and see George Dillon perform a one man show. (“He gets naked,” she said.) I didn’t know who George Dillon was, but, for some reason, I eagerly agreed. I loved the show for the same reason George Dillon has been wowing audiences ever since: his performances are transporting, subtle, spellbinding and human. I had been meaning to see George Dillon again ever since… and finally, last night, I did.

The Man Who Was Hamlet is about the life and rakish times of Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford. He’s a man whose early life has a little of the Dane in it, with his father dying, his mother’s hasty, unseemly remarriage and an incident where he accidentally stabs a servant – hidden, spying behind a hedge. When, later, the well educated, worldly de Vere meets an illiterate William Shakespeare, the parallels start to make sense.

Did de Vere – a patron of the arts, player and playwright – write the plays we now attribute to Shakespeare? Unlike Shakespeare, he had the necessary education, means and motivation. In addition to those facts of circumstance, the play makes a strong case, peopling de Vere’s life with characters and dilemmas that echo familiar Shakespearean themes. It’s very cleverly done. Nothing is decided, just suggested.

The more Shakespeare you know the more allusions and references you will get, but as a piece of historical fiction a la Phillippa Gregory it’s still captivating and fascinating. In the strange, distant world of Elizabethan England, complex mores could lead two men of differing rank to duel to the death over who got to play tennis on a particular court. Even without the Shakespeare question hanging over the life of Edward de Vere, it would still be a fascinating play. Dillon shows us the man as a noble, captive, soldier, lover and favourite of the Virgin Queen – with many a salacious nod to just how much of a favourite de Vere may have been.

And Dillon tells us this story with nothing but himself and a couple of props – including a skull which he never touches. His performance is all you need to transport you back 500 years. He is compelling, charismatic, wry and moving, showing us every side of this man who is a little bit Lord Byron, a little bit Errol Flynn and maybe more than a little bit William Shakespeare.

At the end of the play, Dillon shushes the audience and steps out of character to give his own recommendations for a range of other fringe shows he has enjoyed. It’s a sweet and generous gesture, and I am delighted to wholeheartedly recommend his show in return.

Mathilda Gregory, FRINGEGURU.COM, 20th AUGUST 2010

Using a cut-and-paste montage of Shakespeare’s lines – both as direct quote and in paraphrase – George Dillon reveals the scandalous life of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Or should that be lines attributed to Shakespeare, as de Vere is the leading alternative candidate for authorship of Shakespeare’s works.

It is a clever script, which finds a line through de Vere’s life that echoes that of Hamlet, while using every aspect of Shakespeare’s work, from the sonnets to the plays.

It even brings a young glove-maker’s son into the frame, who de Vere advises to get a schooling and who reappears, rejecting de Vere’s advice on writing a sonnet, and finding employment holding de Vere’s horses.

Dillon puts in a masterful performance, drawing in all manner of Shakespearian acting styles to portray his philandering, foppish, arrogant toff, an adventuring swordsman who was a favourite in the court of Elizabeth.

Denise Evans’ direction is strong, but could allow Dillon to expand a bit in his more intimate side. Charlotte Glasson has created a portentous score that is the perfect appropriate underpinning of Dillon’s style.

An inventive in-joke that will amuse Shakespearian scholars but which, despite Dillon’s towering stage presence, will bemuse those completely unfamiliar with his work.

Thom Dibdin, THE STAGE, 20th August 2010

GREAT DANE

For centuries scholars have disagreed about the authorship of the most famous plays in the world. It’s argued by some that these masterpieces couldn’t possibly be the work of a poorly educated, non-cosmopolitan Warwickshire lad called Will Shakespeare. Many have been thought to be the ‘real’ writer – Christopher Marlowe, Francis Bacon, William Stanley, even teams or groups of writers. Perhaps the strongest ‘candidate’ is Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford.

George Dillon takes this as his premise for this excellent one-man show. His twist on the myriad theories is that not only was de Vere Shakespeare, but his own life was a model for the most famous character in the canon, Hamlet. Hence we begin with Dillon is full Hamletian garb fencing to an atmospheric soundscape. I have to confess that my heart sank a bit at this stage – the show is an hour and twenty five minutes and I thought it was going to be a hard old stint of versifying and posturing. How wrong I was.

Dillon is a consummate performer. He takes us through the entirety of his subject’s life, from his first entrancement at theatre and players, through the death if his father, through being taken on as a ward by the most powerful man in England, William Cecil. Indeed, compared with Shakespeare’s life, of which we know very little, The Earl of Oxford was an extraordinary public superstar. He went on to murder a spy, fall in love with several women and father many children illegitimate and legitimate (mostly by women called Anne – why are all femmes fatales of this period called Anne?). He fought in the Armada, had an affair with Queen Elizabeth (allegedly) but disappeared from public life not long after.

The premise that he wrote the Bard’s plays is not really explained here. There are (fictitious) scenes where he meets the young Will as a boy and later as a ‘bumpkin’ adult. But we never hear of him having meetings about plays, or attending rehearsals or even going to the theatre to see them performed. What we do get is wonderful acting from Dillon, who didn’t fluff a single line. Most importantly in a one-man show (when you know no one else is going to come on to liven things up) there is also great wit and wonderful gags. Just when you think he’s going into full, overblown ‘Shakespearean’ mode he pricks the bubble perfectly with a laugh. He plays, of course, all the other characters, and manages some moving and funny dialogue beautifully, no mean feat when you’re the only actor in the scene!

Directed imaginatively by Denise Evans, with original music by Charlotte Glasson, this is worth seeing both as education and entertainment. As to the contention about authorship of the plays, I remain unconvinced. There seems to be only conjecture here. It is remarkable that we know so little about the man from Warwickshire, given he was recently voted the second most famous person ever. In the end, though, does it really matter? We have those thirty plus plays, all good, some great and a few utterly unchallenged by any writing, in any language, ever. As my old English teacher used to say when we brought up the question: ‘Shakespeare didn’t write the plays. It was another man called Shakespeare.’

Robin T Barton, BROADWAYBABY.COM, 23rd August 2010

If history and theatre is your forte, and you are only able to see one show this entire Festival, it has to be “The Man Who Was Hamlet”. You will be amazed, delighted, amused and shocked as you watch George Dillon acting as the scandalous Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, in a brilliant production in which he not only performs, but which he actually wrote! Easily one of the best shows of the Fringe, the audience explores the life of Edward, his father’s death, his years being raised by and living in the home of Queen Elizabeth I’s main adviser, William Cecil, through his outrageous life and antics.

A master storyteller and amazing actor, Dillon takes the audience through the main life events and associated emotions of the Earl, from passion to grief, excitement to irritation, while they sit so enraptured that you could hear a pin drop. Dillon uses his hands, movement, body (sword) and accents well, also playing the parts of the different characters he refers to, including the stoic Queen Elizabeth I, which has the audience collapsing with laughter.

This is a highly amusing account, with many hilarious anecdotes, yet encompasses what seems like every human emotion imaginable, and the audience feels like they are taking an emotional roller-coaster ride, as they go from laughter to pain, grief to insanity in what seems like a moment. Dillon’s performance is five stars and more, his eye contact with the audience members draws them into the story, and he is thoroughly spell-binding to watch. The music, sound and lighting effects in this production are absolutely brilliant, changing the mood and making all the difference. This production cannot be admired, complimented and recommended more. Dillon is an exceptionally talented man, and Hairline will be first in the queue for tickets if he is back at the Fringe in 2011.

Sandi Hunter, HAIRLINE.ORG.UK, 27th August 2010

George Dillon’s solo piece, The Man Who Was Hamlet, offers us Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford – a candidate for the man who wrote Shakespeare’s work, if William Shakespeare didn’t. In Dillon’s highly talented hands, de Vere is an enigmatic, engaging, self-absorbed, arrogant, brave and witty gentleman of Elizabeth’s court, one whose life and skills fit him for the creation of Hamlet – on that, of course, we must make up our own minds, and Dillon’s de Vere never stakes a direct claim on the Bard’s works even while excellently making use of his words.

Lighting changes, both subtle and dramatic, create settings and atmosphere for this one-man, three-propped (skull, book and rapier) show in shades of black and white, with fine use made of shadows cast. Dillon explores his character’s own shades and shadows in a performance as intriguing as it is riveting. He seems to send his voice forth first into whichever new scene or character is arriving and then draw the rest of him through to inhabit the new creation. Occasionally, this vocal usage starts out as rather extreme, but every time he manages to bring it into believable and engaging truth shortly thereafter.

From his initial display of sword technique, through teasing verbal thrusts and emotional tumult, to the audience’s final sense of something profound having been witnessed, George Dillon – in The Man Who Was Hamlet – performs an engrossing solo show well worth one’s time and attention.

Danielle Farrow, EDINBURGHSPOTLIGHT.COM, August 2010

“Now there comes a time when traipsing around Edinburgh from venue to venue when you hope you might just catch a glimpse of something that makes the whole festival worthwhile. Here is a young man who does just that – in the prime of his art delivering a performance which he also wrote and brilliantly too. He plays Edward De Vere, the prime contender for the writer of Shakespeare’s works.

Watching this I felt I was in the presence of a 16th century aristocrat. This actor, on the stage for an hour and a half, gave one of the most compelling performances I have seen at the festival.

I’ve known George for many years and this performance is amongst the best I have seen – a lesson in the art of acting for any up and coming thespians.”

Steven Berkoff, August 2011

It’s not Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, whose face was the first on an English banknote, but William Shakespeare – The Bard himself. But what if Shakey had not written the plays, the sonnets, the phrases that wove the very fabric of the English language?

In his one-man show, George Dillon is Edward de Vere, all manic energy, aristocratic intriguing and royal schmoozing. As we hear of his rollercoaster life – with its uncanny parallels with that of Hamlet – there’s plenty of in-jokes, as the celebrated lines crop up out of context. “To be or not to be” is just a musing question; “antic disposition” a handy description; and there’s also a young, slightly mad girl singing a bawdy song to remind us that there’s more to Hamlet than The Prince.

It’s not absolutely necessary to be familiar with the play to enjoy the performance, though it certainly helps. Dillon contorts face and body to become an old courtier and, yes, a young Shakespeare and he’s never more than five minutes away from another slice of darkest humour, as he gets the credit for the Armada’s defeat or is released from The Tower on a queenly whim. Like The Tragedian (with which it is in rep), The Man who was Hamlet rewards intellectual engagement with a time long past, with food for thought about the mores of today.

Gary Naylor, BROADWAYWORLD.COM, 10th June 2011

This is the story of a man, who may have been two men, plus another man, plus a man who may have been historical, or modelled on the other man.

“Confused? You will be…”

I’m not usually huge on one-man shows. I’ll admit it. A performance has to be pretty damn gripping, and the material has to be very strong, to carry a show with only one person on the stage. But last night I went to see a one-man show: The Man Who Was Hamlet, both written and performed by one George Dillon. (His publicity says he has been doing solo shows for twenty years but he hardly looks old enough; my friend and I had a conversation afterwards, hypothesising that he could “conceivably be a young-looking 40, he could have got started at 18…” Turns out that if you piece the info together he’s probably eight years older than that, and has been working with Berkoff intermittently since 1986. Ninety minutes of lunging, prancing, fencing, rolling over and dying, and he was still standing at the end! Except for the death bit. I clearly have to get fit.)

The show’s apparently been wowing audiences in Edinburgh for a couple of years – I can see why – and is now doing a little tour. It’s currently at the Riverside Studios in Hammersmith, as part of their Steven Berkoff Presents… season. (On another aside, that’s two Berkoffs for me in only a week! Last Sunday our man unveiled a bust of EA Poe on the front of the Fox Reformed wine bar in Stoke Newington Church St – the site where young Edgar, aged ten, was fostered and educated by Mr Allen while his family travelled – as part of the Stoke Newington Literary Festival. My friend and I were so close we were practically in the photographs.)

But the play’s the thing – and what a play. A monologue life review in the person of the 17th Earl of Oxford, 1550-1604, doesn’t sound perhaps all that exciting. But make that earl a rake and spendthrift, courtier to Queen Bess, player in the burgeoning theatres, the aristocrat closest to the writers of the day – and the most credible candidate in the Shakespeare identity parade – who killed a man in a fencing accident while still in his teens – and it becomes a different matter.

Incidentally. Edward de Vere had a house in Stoke Newington Church Street, sadly no longer standing, right next to where my dentist is. He died there and is said to be buried in Hackney. But George Dillon shamefully leaves this salient point out of his play.

The play never says that Oxford wrote Shakespeare. A difficult feat, to put it in the first person and sidestep the main question, but as I said, there’s a lot of parry-&-thrust. The words are a clever amalgam of Dillon’s, Shakespeare’s, and indeed de Vere’s. The Shakespeare lines are ingeniously woven in and even form a framework for the character development of the protagonist; there is a bit of business when young Edward imitates his guardian, the Queen’s advisor Cecil (later Lord Burghley), giving his “dull man’s philosophies – a [sneers] politician’s philosophies…” which include things about not lending to your friends in case your own fortune be forfeit, and being true to yourself at all times so none can impugn you wrongly, etc – very cleverly done, and of course in his career at court the maturing Oxford must adopt these politicians ways… it’s VERY well done.

It is written in Elizabethan form, in wonderful iambic pentameters that go in and out of prose, and in one or so cases I wasn’t sure if I even heard a sonnet. There is one point when, imprisoned in the Tower and speaking very strong poem about his lover Ann Vavasour, he has to do an awkward line break/rhyme/sense thing, but my friend didn’t notice it. She’s an actress, not a poet.

It has struck me before, by the way, how much more intimate the actors are with Shakespeare than the poets. The poets love him, revere and fear and all that – but the actors inhabit him. It’s a little shaming to the poetry world, I always think. Certainly, poets distrust actors when they start trying to recite verse, because they invariably start acting it – taking the power away from the words and diverting attention to themselves. (Witness Fiona Shaw’s Waste Land, for example, though I know several people who loved it). (And more on that soon.) Poetry is made to be spoken, but it’s hard not to think it’s a sign of our current poetry-nervousness that when people really try to do it, they suck all the oxygen out. No one knows what to do with it… Shakespeare is different because his plays were written to be spoken as plays, and in the least poetically conducive, most rollicking scenarios.

This little one-man show is also rollicking, in exactly that sort of Elizabethan way. (It’s also, as it should be, a memento mori. There are three props: a book, a sword, and a skull.) There are some big laughs, not least on the two occasions when the earl travels through “er – Warwickshire…” and meets a yokel with a large, egg-shaped protuberance on his head. Dillon acts out the yokel (both as a piping child and later as a young man, with churl’s voice), to roars of laughter form the audience. He also does a brilliant little turn as the Pope, excommunicating the Queen. (The Queen herself is a major character, gorgeously portrayed. In his way, George Dillon is the Queen.)

There is a very funny sub-story about his rivalry with Sir Philip Sidney (similar to the rivalry with Marlowe in Shakespeare in Love), which is brilliantly done once again, but – in the only missed trick I could find in the piece – it just fizzles out, just at the point when Sidney is killed in battle and gains glory and honour – just at the point where – but no, no spoilers. But it could have been both a dramatic and a very comic moment.

As for the central character, our Earl, he is utterly brought to life – wielded up from death to play his play, and then returned to it and given a real personality. I wouldn’t say the play says that Oxford is Shakespeare, but I wouldn’t say it doesn’t. It gives us a metaphysical conundrum, with the threads of argument woven in rather than untangled. It’s a gorgeous jeu d’esprit, and an intensely clever piece of work, and if I were you I would go see it forthwith.

Katy Evans Bush, BAROQUEINHACKNEY.WORDPRESS.COM, 12th June 2011

“To be or not to be” is a question George Dillon never has to consider. This exceptional piece of theatre entrances the audience from the beginning. His one-man show tells the story of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, who some believe to be the true William Shakespeare. Dillon’s expert use of mannerisms, body language and facial expression make his Queen Elizabeth convincing in every way. In each moment of de Vere’s life, every character he meets is portrayed with passion and grace; you find yourself forgetting it is just one man. This gifted actor’s old English medieval story is told in the literary style of the age. A gripping Shakespearean performance by a fantastically talented actor.

Eleanor Pender, THREEWEEKS.CO.UK, 27th August 2011

I try not to overuse the phrase “tour de force” because I think that it is typically made commonplace as reviewers rush to use it in the depiction of nearly every single performer show. Yet, George Dillon, a star of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival who has descended upon the Atlantic Fringe Festival this week with four very distinct one man shows, gives me no choice but to herald him a “tour de force” and to mean it from the bottom of my heart…

The first show that Dillon performed at the Neptune Studio Theatre was The Man Who Was Hamlet, a one man Elizabethan history play telling the story of Edward de Vere, a scandalous ex-courtier of Queen Elizabeth whose life is strangely reminiscent of Shakespeare’s famous Hamlet. It is also suggested that this brilliant adventurer, who killed a servant, travelled abroad, was captured by pirates, fought the Armada and was imprisoned in the Tower of London, who kept two companies of players and was a playwright and a poet, but disappeared from history for fifteen years before his death, just around the time that “William Shakespeare” began penning plays, may be the true author of the great works accredited to the Bard of Stratford on Avon. To read more about this conspiracy theory you can head on over to this page.

The first thing that is so striking about this play is the script, and specifically its language. To construct a character who was so well educated, witty, arrogant and impish and then to suggest that he has the poetic skill to be the mastermind behind such a play as Hamlet, Dillon must be able to capture Shakespeare’s modes of speech, while carving out a specific personality and character that makes de Vere radically different from our typical representations of William Shakespeare. At the same time, since it is obvious by de Vere’s outrageously long list of exploits, debauchery and spirit of roguish frivolity, Dillon must also do him justice in making him richly fascinating, multifaceted and wildly fun to watch. He does all this beautifully. In fact, he is even able to weave Shakespeare’s own text in amongst his own and it never sounds a bit out of place, only more familiar.

It is clear, especially the more George Dillon shows that I see, that he has a distinctive acting style and it is one that is very Brechtian. In this play he manages to play a slew of characters, rooting himself specifically in de Vere, while having these characters narrate the events to us. His mode of acting in this play is always larger than life and in his exuberance he captures both the grandiose Elizabethan world, where duels and murders can spontaneously erupt within moments as well as suggesting the playing style of the actors of the time. It is appropriate that Dillon use this style, for “realism” as we know and understand it, had not yet been invented, and this method of performing creates a mood and ambiance which roots us strongly in the context of this story and this man and his parallels to Shakespeare’s work. Throughout, as in all Dillon’s shows that I have seen so far, I felt as though he was brilliantly paving the way and encouraging the audience to really delve with him into the material and to ruminate and contemplate its significance far beyond the curtain call.

Amanda Equality Campbell, TWISITHEATREBLOG.COM, 11th September 2011